Apologies faithful readers – those of you who know me well, know that I have been dealing with a great deal of personal issues and preparing for the summer PBL Math Teaching Summit, so I have taken a small hiatus from blogging for a while. However, with that under control for now, I turn to reflecting on something that happened in class the other day and its relation to a great article I retweeted that was on TeachThought’s website the other day entitled Helping Students Fail. I have been giving a lot of thought this year to the idea of Grit and Problem-Based Learning which has intrigued me for a while. However, this article is one of the few I’ve seen that really speaks to some concrete steps that teachers can take to aid students on the journey of dealing with making mistakes and viewing them in a positive light.

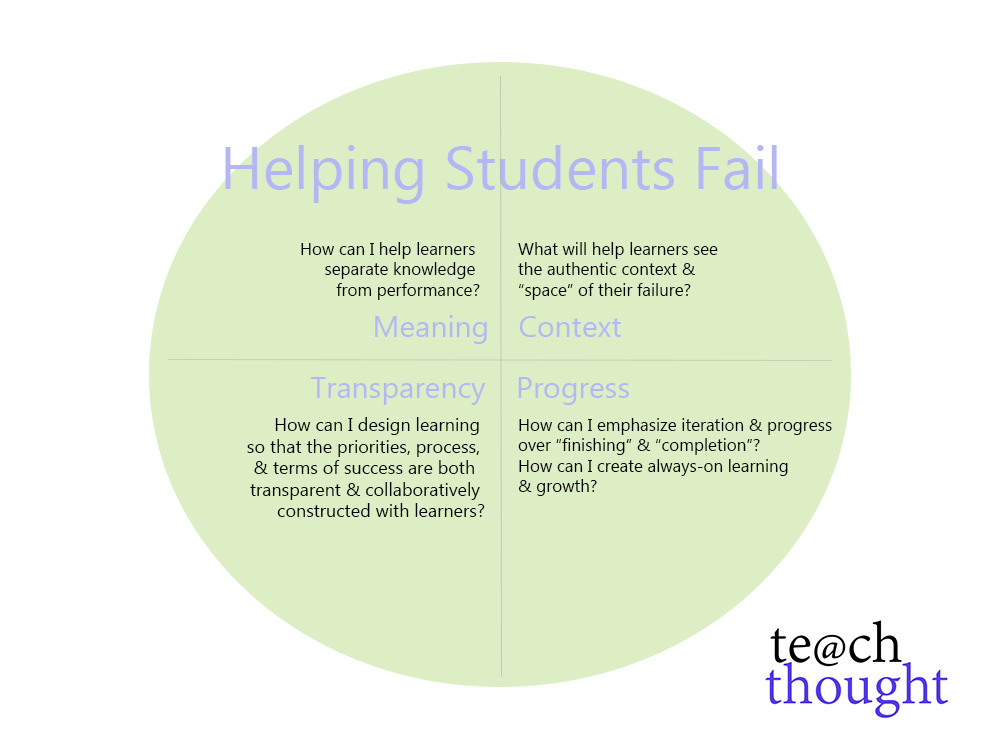

I love the framework that the author gives here:

Breaking the struggle into these four aspects of learning is very interesting to me (of course with respect to the PBL Classroom). It dawned on me while reading this article that this is a continuous and completely ongoing process of learning to fail that happens. It is so ubiquitous that the teacher and students are probably not even aware of it (or are so aware of it that that’s where the discomfort is emanating from). It is so ubiquitous that I needed this framework for me to be able to even have it spelled out for me.

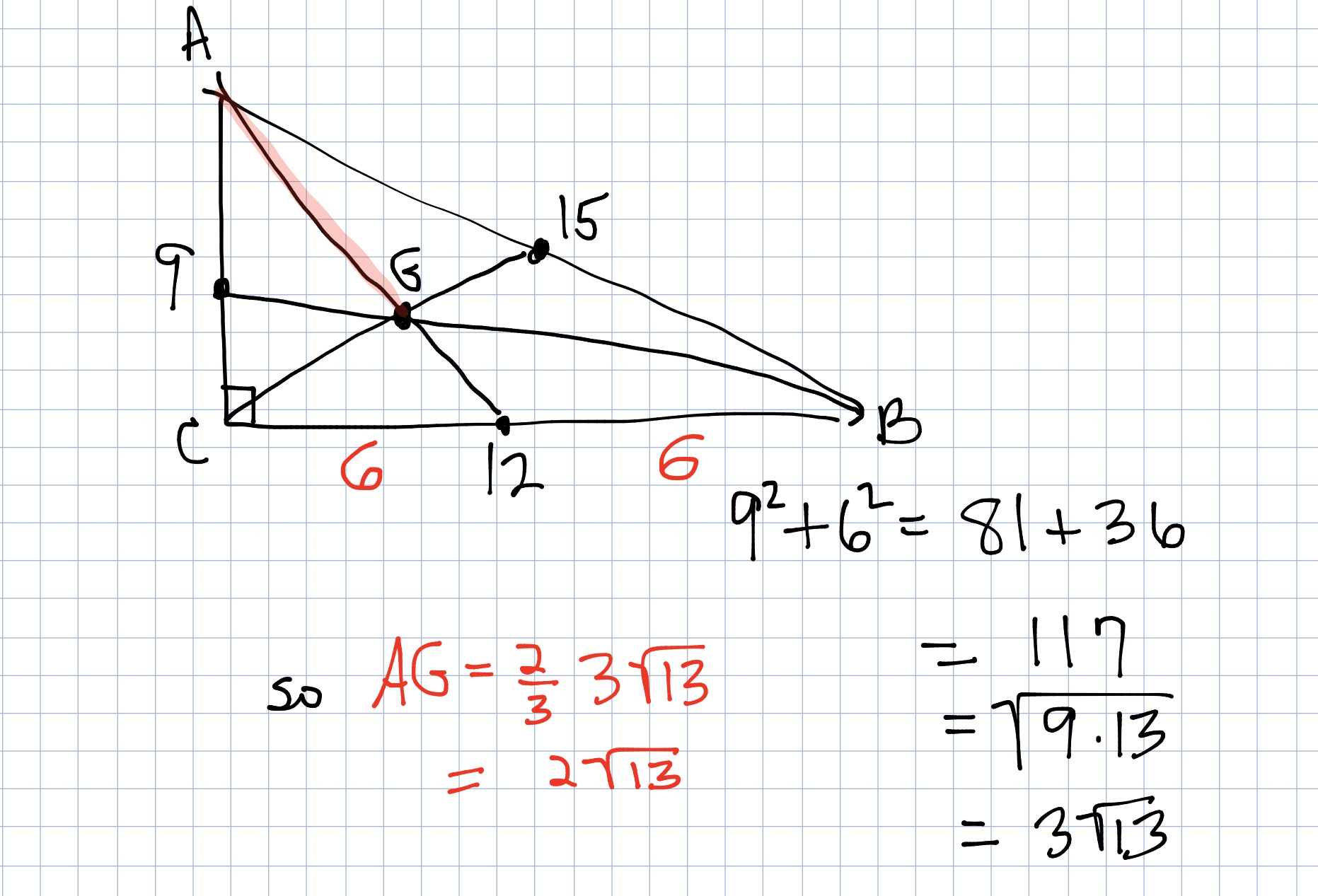

1. Meaning: In the PBL classroom, meaning is shaped everyday – the explicit separation between knowledge and performance is spelled out in discussion and the way students are asked to share their attempts at problems. Jo Boaler might have spelled it out best in her paper desribing the Dance of Agency, where she explained the importance of sharing what she called “partial solutions.” Using this language is really important to make sure that students don’t feel the need to have a complete solution when they present (because no matter how many times I say it, they still say, “Is it OK if it’s wrong/”) In their mind, they feel their presentation is a performance. However, the other day I had an interesting experience while students were presenting. We were doing this problem in class and I had assigned two girls to present their ideas together:

A triangle has sides measure 9, 12 and 15 (what’s special about this triangle?). Find the distances to the centroid from all three vertices.

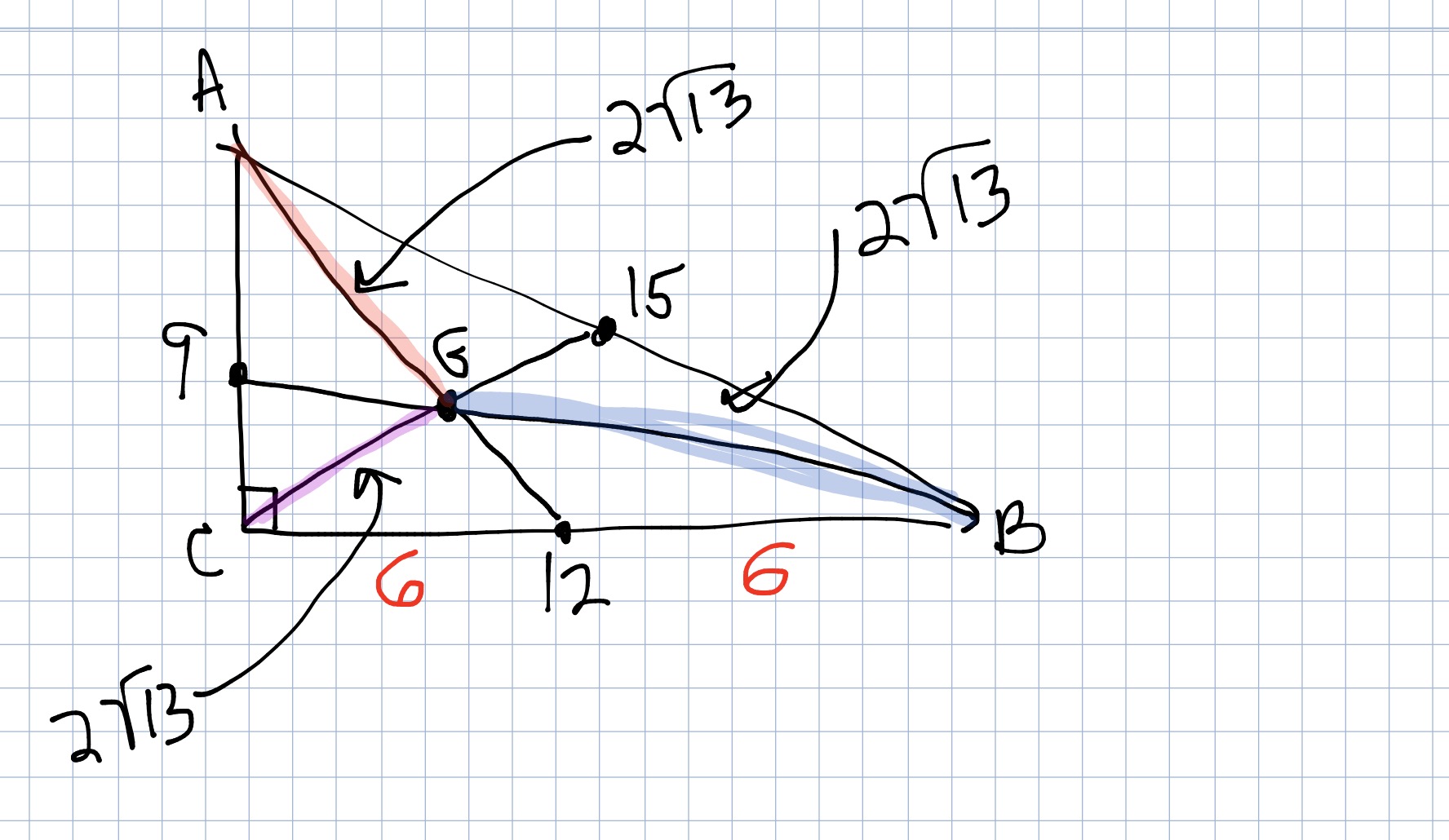

The day before we had done a problem very similar to this with an equilateral triangle of sidelength 6 and the presenter had realized that he could connect this problem to the work we were doing with 30-60-90 triangles. He then applied the Centroid Theorem which states that the centroid is 2/3 of the way from the vertex along the median. So when the girls presented, they did this:

It was great that they connected this problem to the previous day’s presentation where all of the distances were the same (I’m always asking them to look for connections). However, when I asked them the question of whether they expected those distances to all be equal, they had to think about that. We put the question out to the class and it started a great discussion about why sometimes they were the same and sometimes they weren’t. I won’t go into the whole solution here since the correct answer is not the point of this blogpost but what happened that evening is.

It was great that they connected this problem to the previous day’s presentation where all of the distances were the same (I’m always asking them to look for connections). However, when I asked them the question of whether they expected those distances to all be equal, they had to think about that. We put the question out to the class and it started a great discussion about why sometimes they were the same and sometimes they weren’t. I won’t go into the whole solution here since the correct answer is not the point of this blogpost but what happened that evening is.

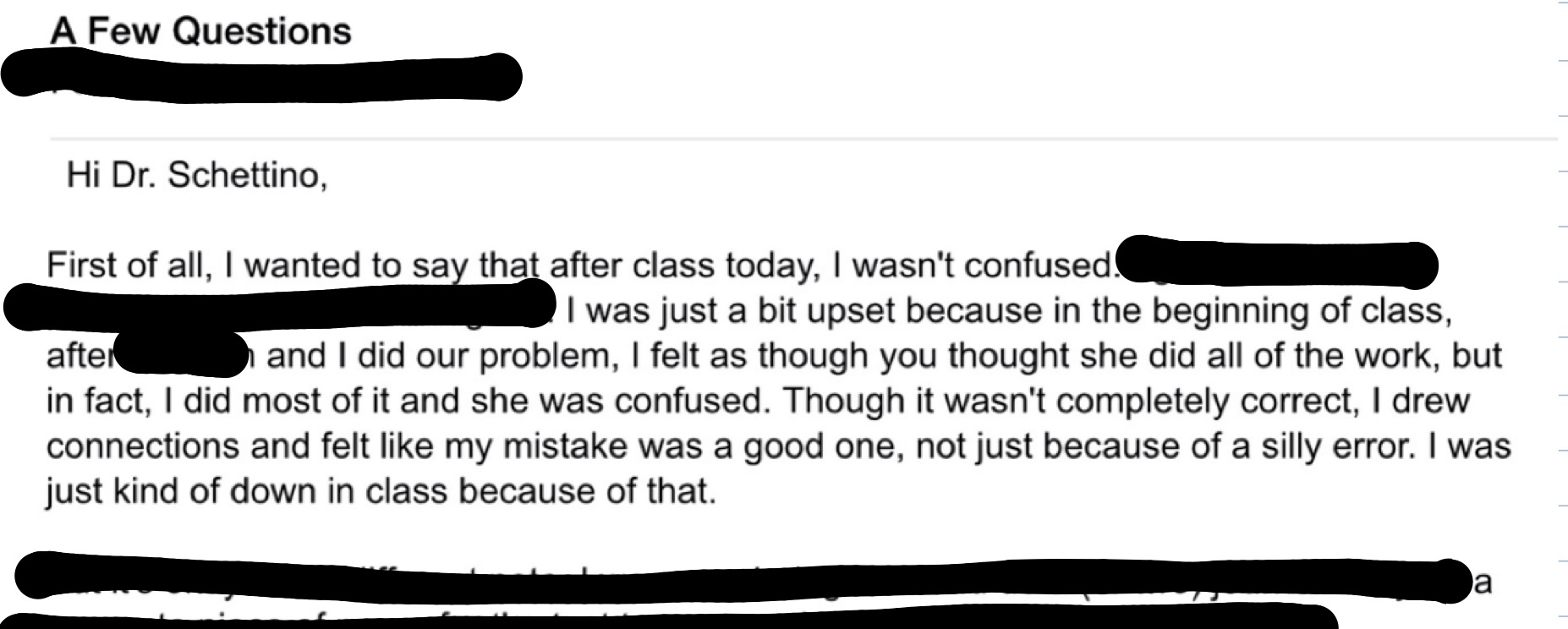

Later on that night, I received an email from one of the girls who was part of the presenting team. At the end of class, I had noticed that she seemed very quiet and I had asked her if she was confused about something else we were discussing towards the end of the class when the bell rang. She had said no and left class very awkwardly.

This is what she wrote to me:

I had been working so hard to make students feel comfortable making mistakes that I wasn’t paying attention to who had made the mistakes and that they were actually comfortable making the mistakes and proud of making those mistakes and wanted credit for making those mistakes! I was dumbfounded. I just couldn’t believe it. My perception of (at least) this student’s ability to be comfortable with being wrong was so different than what her’s was. She was proud that her “mistake was a good one” and not just a “silly error” and I needed to give her the credit she deserved for taking a risk. I learned such a great lesson from this student on this day and I owe her so much (and don’t worry, I told her that in an email response)!

The separation between knowledge and performance has been made clear to at least some of my students and I am going to keep doing what I’m doing in the hope of getting this message to all of them.