So the spring term means two things for my Honors Geometry kids – the technology inquiry project and looking at the French Garden Problem. So for those of you who are not familiar with both of those I’ll try to quickly fill you in while I talk about how they just happen to so coolly (is that an adverb? if not I just made it up) overlapped this week.

My Spring Term Technology Inquiry Project is something I came up with three years ago when I really wanted a way to push my honors geometry students into thinking originally while at the same time assessing their knowledge of using technology. I did a presentation last year at the Anja S. Greer Conference on Math, Science and Technology and the audience loved it. Basically, I give students an inquiry question (one that I attribute to my good friend Tom Reardon) that they have to work on with technology and then they have to come up with their own inquiry question (which is, of course, the fun part) and explore that with technology and/or any other methods they wish. I have received some pretty awesome projects in the past two years and I don’t think I am going to be disappointed this year either.

The French Gardener Problem is famously used in my PBL courses at the MST Conference as well. Everyone who has taken my course knows the fun and interesting conversations we have had about the many ways to solve it and the extensions that have been created by many of my friends – an ongoing conversation exists somewhere in the Blogosphere about the numerous solutions – In fact Tom sent me a link just last fall to a more technological solution at Chris Harrow’s blog. (We’re such geeks). Great math people like Phillip Mallinson and Ron Lancaster have also been drawn in by the attractive guile of the The French Gardener Problem. In this problem, the main question is what fraction of the area of the whole square is the octagon that is formed inside (what is the patio for the garden)?

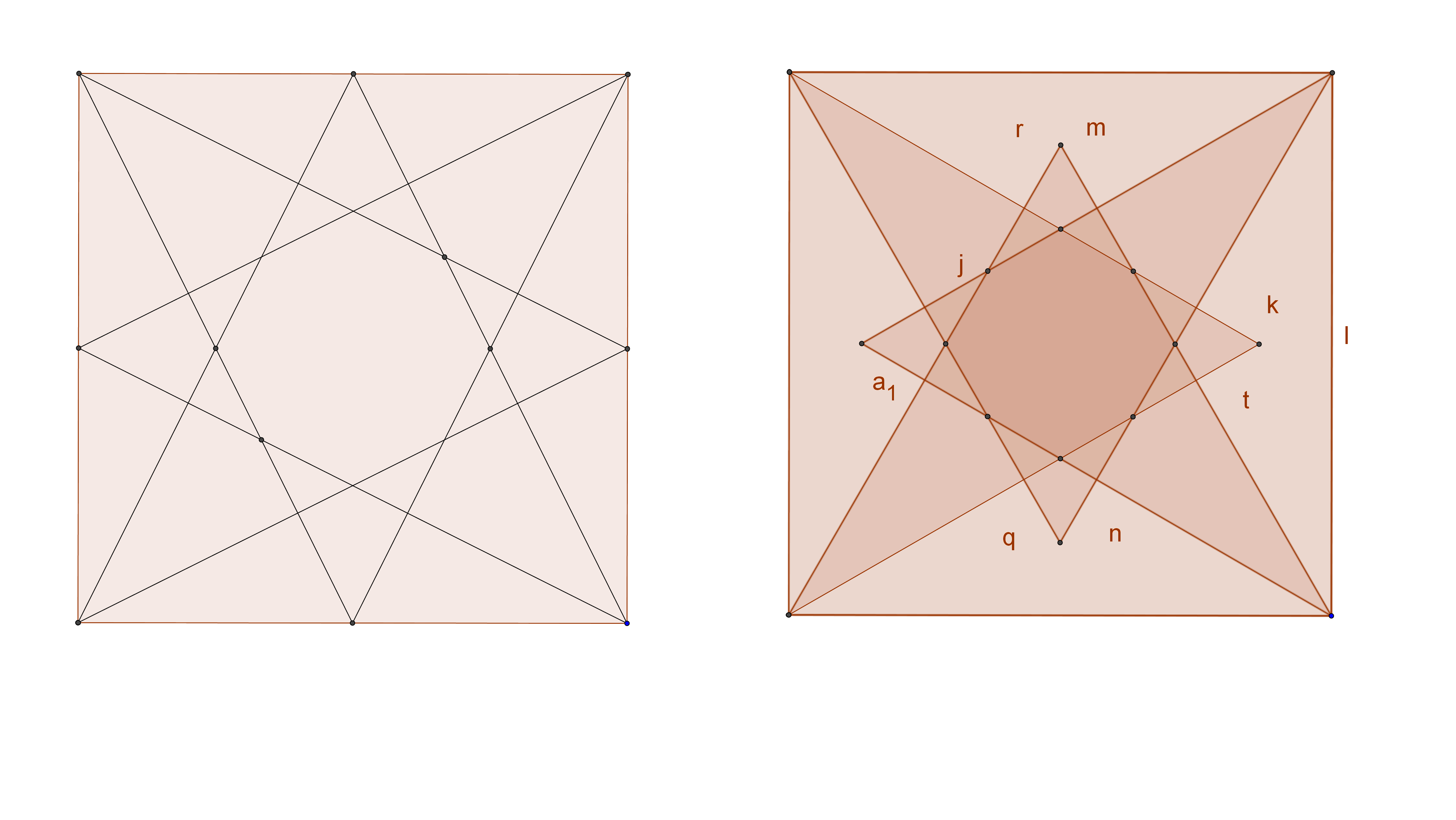

So the other night, after we had worked on this question in class for a couple of days and the students had meet with me in order for me to approve their original inquiry question, a student stops by to discuss his question. John starts off with, “I can’t think of anything really. What I had wanted to do, someone else already claimed.” (I’m not letting them do a question that someone else has already decided to look into. So John sits in my study and thinks for a while. I told him that this part of the project was supposed to be the fun part. I gave him some thoughts about extending some problems that he liked. He said he had liked the French Garden Problem and thought it was really cool. So I went back to some of my work and he started playing with GeoGebra. Before I knew it he starts murmuring to himself, “Cool, cool….Cool! It’s an octagon too!” I’m thinking to myself, what has he done now? I go over to his computer and he’s created this diagram:

I’m asking him, “What did you do? How did you get that?” He says that he just started playing with the square and doing different things to it and ended up reflecting equilateral triangles into the square instead of connecting the vertices with the midpoints as in the original French Garden Problem. Then he started seeing how much of the area this octagon was and it ended up that it was……you don’t think I’m going to tell you, do you?

Anyway, it just made my night, to see the difference in John when he came by and the by the time he left. He was elated – like he had discovered the Pythagorean Theorem or something. I just love this project and I would encourage anyone else to do the same thing. Leave a comment if you end up doing it because I love to hear about any improvements I could make.