Yesterday we had a speaker in our faculty meeting who came to talk to us about decision-making process in our school. He spoke about the way some colleges, universities, independent schools are very different from businesses, the military, and other governing bodies that have to make decisions because we are made up of “loosely-coupled systems.” These are relationships that are not well-defined and don’t necessarily have a “chain of command” or know where the top or bottom may be. They also don’t necessarily have a “go-to” person where, when a problem arises, the solution resides in that location. The speaker said that this actually allows for more creativity and generally more interesting solution methods.

About mid-way through his presentation he said something that just resonated with me fully as he was talking about the way these systems come to a decision cooperatively.

“The difference between mine and ours is the difference between the absence and presence of process.”

Wow, I thought, he’s talking about PBL. Right here in faculty meeting. I wonder if anyone else can see this. He’s talking about the difference between ownership of knowledge in PBL and the passive acceptance of the material in a direct instruction classroom.

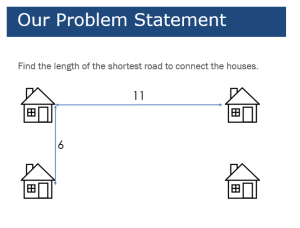

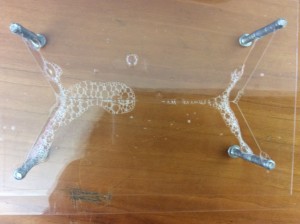

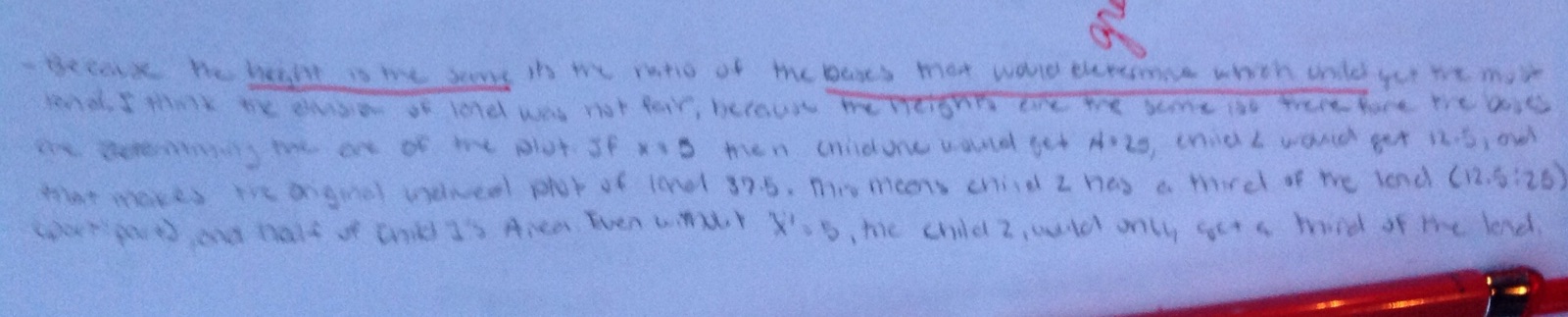

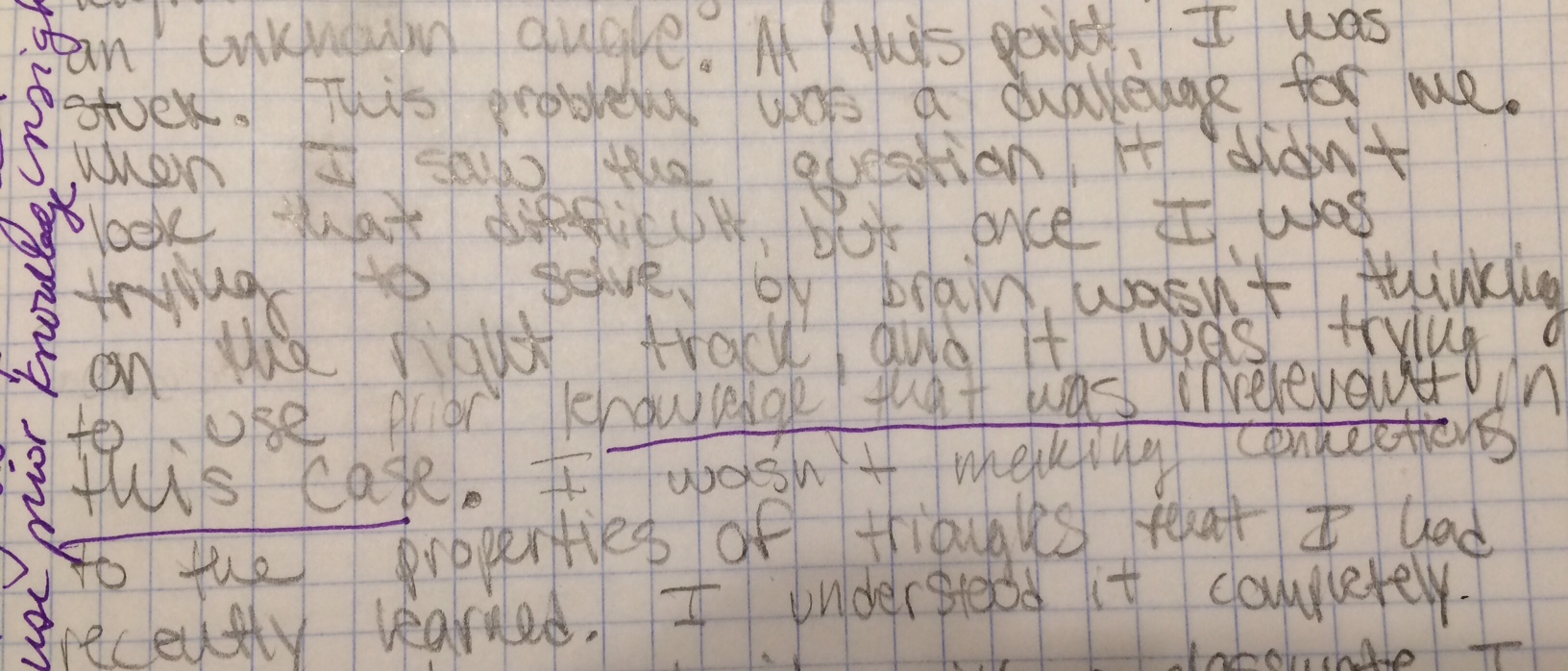

Part of my own research had to do with how girls felt empowered by the ownership that occurred through the process of sharing ideas, becoming a community of learners and allowing themselves to see others’ vulnerability in the risk-taking that occurred in the problem solving. The presence of the process in the learning for these students was a huge part of their enjoyment, empowerment and increase in their own agency in learning.

I think it was Tim Rowland who wrote about pronoun use in mathematics class (I think Pimm originally called it the Mathematics Register). The idea of using the inclusive “our” instead of “your” might seem like a good idea, but instead students sometimes think that “our” implies the people who wrote the textbook, or the “our” who are the people who are allowed to use mathematics – not “your” the actual kids in the room. If the kids use “our” then they are including themselves. If the teacher is talking, the teacher should talk about the mathematics like the are including the students with “your” or including the students and the teacher with “our”, but making sure to use “our” by making a hand gesture around the classroom. These might seem like silly actions, but could really make a difference in the process.

Anyway, I really liked that quote and made me feel like somehow making the process present was validated in a huge way!